[Editor’s Note: Rob Peterson is a young engineer working in the trucking industry. He likes writing technical stories about old-school engineering tech like swamp coolers. If you’re also an enginerd who wants to write about car tech, email david@autopian.com. -DT] [image] Let’s have a look at what an air brake system looks like on a big truck.

A Little Intro On Air Brakes Used On Trucks

Some important components of the system include: Air brakes are a totally different animal from hydraulic systems found in passenger vehicles. The obvious difference is that the fluid transferring braking pressure is air instead of liquid brake fluid. These systems hiss and squeal and pop and can make you spill your coffee if you’re dozing off. When starting the vehicle, a crucial pre trip check is watching air pressure build within the system via a dial gauge on the dash. As a safety mechanism, often there is a mechanical spring in the chambers to hold the truck in place if the pressure is low (this is the park brake, or “spring brake,” and is released via a hand control valve in the cabin). As for the service brake/foot brake, it sends pressure to the brake chambers to apply the brakes; it can be a little touchy with little to no pedal travel; some practice and finesse is key.

If you have replaced brake fluid in a car you are likely familiar with the tedious bleeding process. What you are doing is servicing a closed system in which the brake fluid is effectively isolated from the outside world. However air brake systems are open with the compressor sucking up air from outside the vehicle. As a result, moisture content in the air is able to enter the system. This is concerning because this moisture could condense when cold and form ice within brake lines. Jammed up lines could mean locked up wheels or brake shoes unable to actuate.

This problem can typically be solved by draining air reservoirs after drives, integrating an air dryer device, or by having a dedicated “wet tank” that collects water in the system. Additionally, the majority of trucks today are equipped with dual air brake systems. Each system controls half of the vehicle’s brakes as an additional safeguard against catastrophic failure. More in depth analysis of air brake components can be found in this article written by our ever-talented David Tracy. As a side note: David answers a key question, which is: Why are air brakes used? He explains that they are favored in heavy duty applications: David is referring to the air chambers/brake chambers mentioned prior that are sort of bulb-like in shape. Even if you found yourself with a leaking air line, that compressor will keep chugging away to try and replenish the reserves. Whereas, a hydraulic system would bleed itself dry after a few “come to Jesus” pumps of the brake pedal leaving you coasting into hopefully a big pile of pillows. More importantly, the park brake/spring brake will save you in the event of an issue with the pneumatic brakes. From David’s story:

Even though the industry has moved on, if you’re interested in archaic, impractical, hazardous solutions to the whole moisture-in-brake-system problem, alcohol just may be the tool for you.

Using Alcohol To Prevent Brakes From Freezing

Here’s where the HillBilly magic kicks in. You likely already know that Vodka is best served fresh out of the freezer. Despite it being similar in appearance to water, the liquid remains.. well.. liquid when exposed to subzero temps. The freezing point of alcoholic beverages is largely dependent on their alcoholic concentration. Obviously, water’s freezing point is 0 degrees, but alcohol’s is lower than minus 150 degrees. Mix the two, and you’ll end up with a freezing point between those two figures. If you are curious to see alcohol’s low freezing point in action, this science experiment with thoroughly underwhelmed children should suffice.

As I understand it, why alcohol has a lower freezing point than water largely has to do with the atomic properties of the substance. In case you are not aware, this world is made up of clusters of atoms. Solids have rigid structures of atoms vibrating, liquids are freer flowing streams of sticky atoms, and gasses consist of rambunctious atoms bouncing all over the place. The movement of atoms can be described their kinetic energy, which is directly related to temperature.

Whether or not the soup of atoms exists in a solid, liquid, or gaseous state is partly dependent on whether the atoms’ kinetic energy is strong enough to break intermolecular forces. Water forms strong hydrogen bonds between molecules which lends itself to freezing. In the case of H2O, there is not enough kinetic energy to break intermolecular forces at 32°F. Not enough kinetic energy means the bonds dominate and ice forms. However, the types of bonds alcohol molecules form with one another are not nearly as strong, which means kinetic energy overwhelms intermolecular forces until the temperature is brought to more extreme lows. The chances of encountering -173 °F on your delivery route are pretty slim unless Jeff Bezos starts a prime service for residents of Jupiter.

This property is the fundamental principle behind Alcohol Evaporators in air brake systems. Historically these devices are usually used in tandem with air dryers, as old designs were not as effective as ones used today. Moisture that bypassed the dryer could be diluted with alcohol downstream. Air dryers are easy to spot on a truck. They are usually mounted somewhat near the air reservoirs after the compressor and are similar in appearance to an oil filter but flipped up like a Subaru’s and larger in scale. For a brief period of time during the mid 20th century these two devices coupled together were pretty standard procedure.

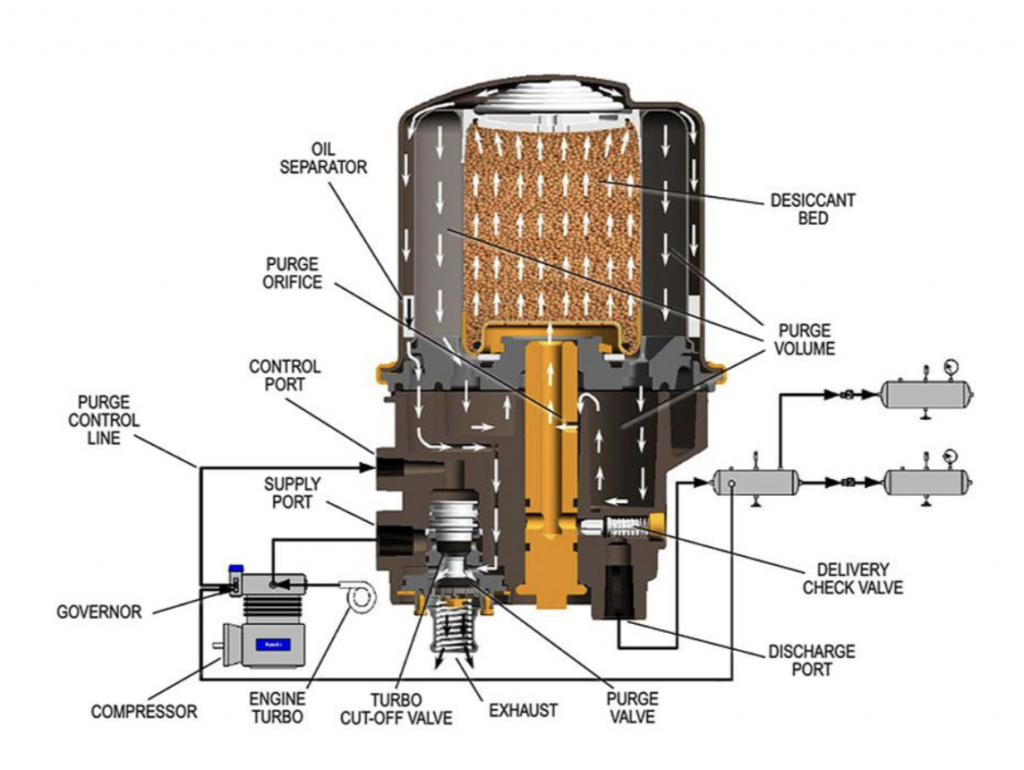

The air dryer itself is fairly fascinating, involving a special “desiccant” whose job it is to trap water from oncoming air. There’s also an oil separator. Check it out: Trucksales.com gets into how a dryer works, writing: The article also mentions a purge cycle in the air brake system that involves opening a purge valve and using air to shoot contaminants out of the dryer. Plus, the writer notes that the desiccant has to be replaced every now and then. The alcohol evaporator is also mounted upstream from the air reservoirs. According to Haldex, compressed air rushes through a series of venturi passages and over the liquid reservoir of methyl alcohol. This interaction mixes alcohol into the air stream (methyl alcohol is hygroscopic (absorbs moisture) and miscible with water (i.e. they mix well)) before exiting through a check valve that prevents back flow.

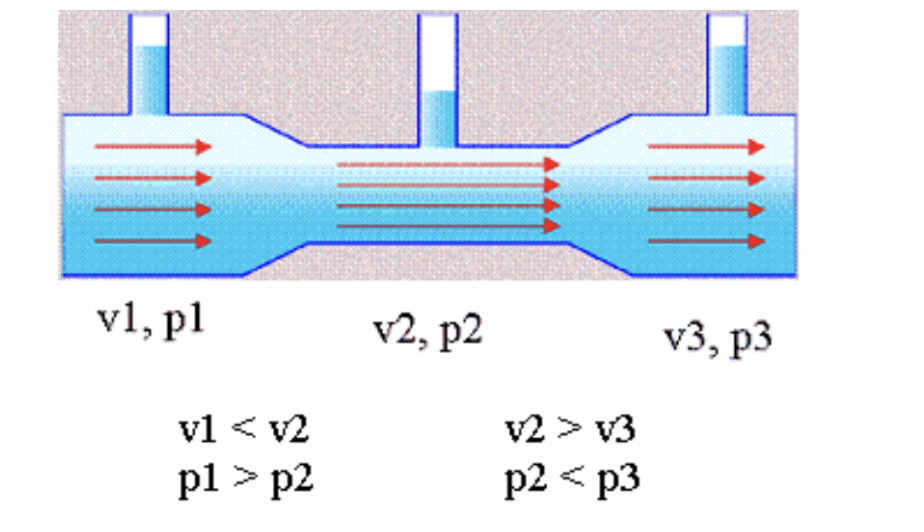

Fluids that pass through a venturi experience a special effect. A venturi is a passage of varying diameter. You can picture it as if two nozzles were joined together at their small ends. While in the larger diameter part of the passage, the fluids are under higher pressure and experience a lower velocity. While in the section with a small diameter, the fluid trades pressure for velocity and it rushes through. This process is also critical to how a carburetor mixes air and vaporized gasoline before combustion. Air from a bowl (or in this case a chamber) is at ambient pressure; the low pressure at the venturi pulls the gasoline (or alcohol in this case) in. Alcohol evaporators — which the maker of the evaporator shown above, Haldex, describes as “automatic vaporizing device[s] for keeping air lines and air reservoirs free of ice” — are not without their flaws. For one, alcohol has a corrosive nature especially when in contact with polymers and adhesives. Eating away at the air hose connections could result in a catastrophic leak on the vehicle, and that’s arguably worse than a bit of ice. There are a number of YouTube videos showing alcohol being poured directly into brake lines to get going in a pinch. However, I can’t advise repeating this procedure in good conscience. Alcohol is also a fairly volatile fluid which can ignite quickly. Jeff Celetano’s article Truck Air Brake System Maintenance on diesellaptops.com tells a cautionary tale about these devices: Jeff reported suffering some hearing damage from the explosion but ultimately is lucky to still have a face. Stories like this are likely why the question remains on the CDL exam despite the devices long being out of vogue. Truckers often move from one vehicle to the next and have to quickly identify little differences in equipment and make a judgment call on the safety of the vehicle. However, if you find yourself operating a truck with one of these devices equipped, they can still be used with methanol-based airline antifreeze. If there is any lesson to be learned from alcohol evaporators it’s that there are many ways to skin a cat. No… wait, leave Mittens alone. I mean, that in engineering there are often a number of solutions available to achieve a singular goal. Often these solutions are layered in a way that increases the factor of safety of a system. Each solution should be measured by its own merits as well as how it can pair with others. If one method fails, there should always be another ready to step in to get the job done. However, in the case of Alcohol Evaporators, I think the alcohol would be better suited for use in a cold drink after a strenuous day of wrenching. Hydraulic brakes – leak in the system, unable to stop. Air brakes – leak in the system, you better get out of the way of traffic before it drops anchor because it’s fail safe (the air keeps the brakes from engaging) and like it or not, you’re stopping. The air brake test is the one part where you can’t make any mistakes, at least in Virginia. Pretty sure other states too (they’re all different which is weird) Now a catastrophic failure that results in an immediate large drop in pressure, can cause them to come on quick and hard, sometimes just the brake that line services. Sorry Mr. Pratchett, had to be done. TLDR: Any substance that is soluble in water will reduce the freezing point and raise the boiling point compared to pure water, when it is dissolved to form a solution. -Rob also, interestingly, it takes a longer distance to stop an unloaded truck and trailer than a loaded one. The suspensions are designed to carry heavy weight and when they are unloaded, they are highly unstable. When you lock up the brakes, an empty trailer will hop and bounce whereas a loaded one will keep the tires planted and stop quicker. I hate hydraulic brakes. The fluid is corrosive to paint, it is usually hydroscopic, and they are very vulnerable to damage, etc. For me Pushrod brakes > Cable Brakes > Air Brakes > Hydraulic brakes. Some fleets install automatic bleeders to accomplish this task. They’re great until they get stuck in the open position, which is common because the valves are underneath the vehicle where dirt, snow and other detritus showers the bleeders constantly. Source: Me. I once drove buses at a ski resort. The log truckers I know call it a drop axle, but that might be a PNW- or logging-specific term. On-site many will lift those axles in low traction situations to increase the weight on the drive axles.